Lecture on protest in Colombia opens seminar on violence and conflict in Latin America

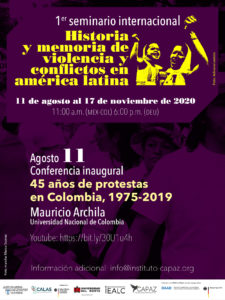

Mauricio Archila Neira’s lecture on protest in Colombia held on August 11, 2020 launched the virtual lecture series of the First International Seminar on “History and Memory of Violence and Conflict in Latin America”.

The lecture series will run from August to November 2020 and can be seen on the YouTube Uninorte Académico channel. An online lecture will be held every Tuesday at 11:00 a.m. (Colombia time) on the historical dynamics and memory of violence and conflicts in countries across Central America and the Southern Cone.

During the opening session, the seminar coordinators explained that this academic space is relevant because it will address the changing realities and problems in Latin America. They highlighted the quality and exchange between speakers and on various topics that will be promoted by the programme.

In association with the CALAS Centre (Merian Centre for Advanced Latin American Studies), the Institute for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Universidad del Norte (Colombia), and the Justus Liebig University Giessen (Germany), CAPAZ convened a renowned group of researchers from Latin America and Europe to take part in the lectures.

Opening lecture: protests in Colombia

Mauricio Archila teaches at the Department of History at Universidad Nacional de Colombia and is an associate researcher at CINEP. His lecture was based on CINEP’s research on social struggles in Colombia since 1975.

Access the video recording of the opening lecture

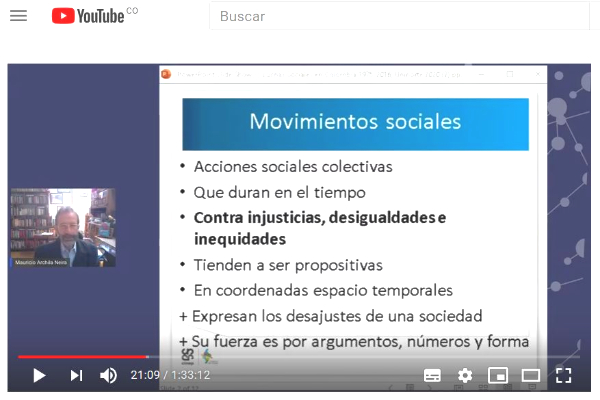

As defined by Professor Archila, social movements are collective social actions that persist in time and correspond to a specific space. They reflect the pulse of democracy, beyond the left or the right. These movements do not stop at resistance or concentration; they propose an agenda and render visible the imbalances in a society.

Three aspects strengthen social movements: the arguments that motivate them; their capacity to mobilise (how many people they mobilise); and the way in which they become visible. Social movement responds to the logic of demands and participation more than to that of elections. Nevertheless, “not every mobilisation necessarily configures a social movement”, explained Archila.

Captura de la ponencia de Mauricio Archila/Screenshot, Mauricio Archila’s lecture

Protests are public in nature and build social bonds, in defence of the right to be different and they seek visibility and resonance through the media and social networks. Some of these features of protest have been affected by the current pandemic.

The trend between 1975 and 2019 shows a close association between social struggle and democracy: the greater the openness to democracy, the more mobilisations there tend to be. Another feature that is evident in the analysis is the rise of social protest in contexts of dialogue with the insurgency. The government of Álvaro Uribe Vélez, which had a more authoritarian tone, marked a break with this trend, explained Archila.

The years 1970-1980

The most accurate statistic is the number of protests, not the number of protesters, noted Professor Archila. In the first years analysed, during the government of Alfonso López Michelsen, there was a boom in social movements, especially among students. His government was the first to follow those of the National Front. President Julio César Turbay Ayala subsequently implemented the Security Statute, a policy of repression and human rights violations. During his government, there was a decline in the number of protests. Among other measures, the Belisario Betancur government promoted political reforms (such as the popular election of mayors), decentralisation and the first dialogues with some insurgent groups. These scenarios motivated action, with an upsurge in protests in the 1980s.

You may like: Un repaso por la lucha social en Colombia de los últimos 45 años (Universidad del Norte, 12.8.2020)

1990-now

The 1990s saw few social mobilisations, despite the initiative of the Constituent Assembly (probably because all efforts were directed at pushing it through). The Ernesto Samper government did not see a surge in protests either, but rather a decline. The year 2013 saw the highest peak of protests on record, especially around the agricultural strike, which was not quickly recognized by the Juan Manuel Santos government. Interestingly, the political opportunity for rural mobilisation of peasants and indigenous peoples coincided with the peace dialogues in Havana. Several sectors were mobilised at that time, not only the agricultural sector. In recent years (2017-2019), it has been mainly students at public universities that have gained social and media visibility.

Actors of the protest

Professor Archila said that the protesters are recognised either by their identity (gender, class) or by the type of claim. He noted that there are more visible faces of protest in terms of identity, for example, women or the LGBTI population.

Peasants, the working class, and trade unions have been traditional actors in the history of protest and protagonists of social struggles. In neoliberal scenarios and economic openness, these actors have not disappeared, but they have lost visibility, although they continue to be great conveners. The violence has also affected the mobilisation of unions, peasants, and social leaders, as their lives in Colombia have been put in danger.

Actors with increasing visibility are the urban population or inhabitants of popular neighbourhoods, who protest against urban public policies, the provision of public services and unfulfilled promises; students, who maintain a visible mobilisation; and the victims of violence and armed conflict, mainly women, whose protest has acquired increasing resonance, especially during and since the government of Álvaro Uribe Vélez. Independent or informal workers are gradually becoming more visible in their struggles related to their working conditions. Professor Archila mentioned that groups such as transporters are not considered social movements but rather groups that lobby the State. Ethnic groups maintain relatively low visibility; however, indigenous protests stand out, in proportion to their population.

Mobilisation factors

The motives for social protest abound. In line with the analysis described above, protests whose motivations are more of a material nature (labour specifications, land claims, housing, and public services) have lost visibility in comparison with those motivated by political, environmental or cultural reasons (defence of human rights, political motivations, failure of the State to fulfil its obligations). In the current government, the most notable aspect was the failure to comply with the peace agreements or with what had been agreed with students and the civilian population in certain regions such as Chocó or El Cauca. Professor Archila made an important clarification concerning this trend: “Colombia has not solved its problems of basic needs, but the dynamics of the war, the dynamics of the conflict have made other factors take priority”.

Agendas, procedures and Colombia’s place in Latin America

Protest in Colombia has two coexisting logics, explained Professor Archila. On the one hand, the logic of the classic agenda of social movements, in places where there is greater concentration of capital and resources. On the other, the logic of the spiral of protest, violence, repression in Colombia’s history, and so on, in the face of the emergence of new sources of wealth (mega-projects or extractivism).

Strikes are the major legacy of social movement; however, mobilisations, protests, and occasional interruptions in public space are usually more visible, less costly and more effective. In the agrarian and peasant sector, roadblocks are a recurrent mechanism used to engender visibility. Non-peaceful forms of protest—such as riots—affect the status quo, yet the trend shows that the power of protest does not lie in violent action, but in its arguments, the scope of its call, and its forms of demonstration.

What happens in Colombia is not very different from what happens in other Latin American countries. We share common structural contexts and trajectories. However, Colombia is a particular case because of the context of the armed conflict, which has lasted longer than in other countries. Protest in Colombia equals putting lives at risk.

Download the complete calendar of lectures from August to November 2020 (.pdf, in Spanish)

Upcoming online lectures in August 2020:

Martha Nubia Bello (Universidad Nacional de Colombia) – August 18, 2020 – More information

Roberto González (Universidad del Norte) – August 25, 2020 – More information

(NW Text: Claudia Maya. English version: Tiziana Laudato)